For a few hours on December 28-29 2017, the BBC reported “Apple apologises for slowing older iPhones down” as the biggest news story in the world.

There are some obvious reasons for news rooms to cover this. Apple is currently the most highly market-valued company in the world, a status which reflects the influence it has on us now, as well as expectations for the future.

Something about iPhone makes it iconic, standing for something bigger than itself. Even though Apple only sells 1 in every 8 smartphones (source: IDC), few would deny the iPhone’s influence ranging from minor tech details, like “do we need headphone jacks?”, to major quality of life issues. Before iPhone, high tech phones were gadgets virtually no one thought they needed. Now more than 2 billion people use smartphones (source: Statista) and probably can’t remember how they managed without them.

But that in itself doesn’t explain why Apple’s unusual press release about a detail of its power management software could feel like the biggest story in the world. I think there’s much more going on than a business tech story. This top 5 list of reasons why is going to start with the tech but land closer to our souls.

5. It’s like Apple just drove over land mines in our heads

I’ve heard reporters mention weeks of speculation about iPhone’s power management, but as an iPhone user since the original version, I’ve experienced a constant question every time a new one comes out. Should I get one? Apple’s answer to this seems predictably “yes”, but what if I’m perfectly happy with the one I have? Apple can tempt me towards a new phone, but would they also do anything to make me less happy with my current one?

For years, people have felt that they might. It seemed to many users like their phones slowed down shortly before a new one came out. “iPhone slow” has peaked as a measurable Google search trend every time a new iPhone has come out. (Source: Statista)

You will find more statistics at Statista

You will find more statistics at Statista

It’s been my experience too. For every good physical reason, like software updates increasing demand on hardware, questions remain which adds psychological pressure.

Why does my phone seem slower even if I don’t update iOS? Am I imagining it because I just want a faster new one? If it’s not my imagination (and I’d prefer it wasn’t because then I might be going mad), what might Apple be doing to my phone? Could they really be making it obsolete so I’ll buy a new one?

“Planned obsolescence” has been much discussed, and strongly denied by Apple. It would probably be illegal. So while many of our experiences made us suspect Apple was slowing our iPhones, their denials made us bury our suspicions to some extent. These never go away completely. They lie hidden, like land mines, waiting to go off if new evidence puts enough weight on them.

In this case, boom. Apple might have wanted to address one issue, the life and health of aging batteries, but the way they did it put pressure right where our old suspicions were. Apple has been knobbling our phones and not telling us! We were right!

4. We always want to be right

This sounds like vanity, but in a complicated world, being right about stuff feels important.

There is much that is hidden in the world which can affect us. So for our health and survival, our heads have to have a model of how the world works, what to expect, and what to do or avoid as a result.

Being right in our assumptions about what’s going on in the world is a hell of a lot easier for us than being wrong. When we feel we know what’s going on, we can be confident in our decisions, spending less time and energy on worry and doubt, and this tends to make us more productive and happy, even if our assumptions are wrong.

Being wrong is a big deal. We’d rather avoid the inconvenience, embarrassment and the feeling that we’ve wasted our time, let alone the pain and difficulty of change.

So we go to considerable effort, even without being conscious of this, to grab opportunities to affirm that we were right in the face of any doubt about this.

In this case, experiences of slowing iPhones led to debates about the reality of this phenomenon every year. For some, physical explanations are enough – battery chemistry is interesting! (For a few of us.) I had experienced the annoyance of unexpected shutdowns caused by weak batteries, and already figured it might be a good idea to deal with this. Turns out, Apple did too. Hooray for being right! Thanks for being so considerate, Apple!

But if the main theory you had was that Apple was secretively slowing your phone down for unexplained reasons without acknowledging this when challenged, you were right too.

The lawsuits against Apple for this don’t come from grateful, satisfied customers who feel right for trusting Apple, but from people who feel right for not trusting them. In some cases, they might be especially angry for feeling conflicted and betrayed. They loved iPhones enough to buy them, and trusted Apple enough to rely on them. Being let down here isn’t just an annoyance but a betrayal of the heart.

3. Trust is becoming a bigger and bigger deal in tech

Increasing reliance on technology isn’t news in itself, but it’s a huge trend. Any development which sheds light on this can feel like a massive story.

Mobile phones inspired many people to trust tech in new ways. Before them, we’d have to make plans before going out. With them, we can adapt as we go, change a meeting time and place, always be contactable in an emergency, always feel close when we are far away. As long as everything works, of course. This requires trust, in batteries, signal strengths and lots of other complex things we can’t directly control.

Smart phones demand more trust. They offer maps and information on the move, so if we trust them, we can land in a new city and feel right at home. They store and process our most personal data, from contacts and schedules to ideas, photos, memories and all kinds of creative expressions. In doing this, they feel like companions, trusted with our secrets, reflecting our experiences, sharing our lives.

Not only are smart phones good at storing and processing things alongside us, they are portals to the massive storage and processing of “the cloud”. From apparently simple storage lockers like Dropbox for our documents to the much more complex processing of data that Apple, Google and others do to make useful services, smart phones host technology which works when we trust it, run by businesses that grow when we trust them more.

I find it a bit frightening even to think about the amount of trust were placing in technology, companies and, ultimately, people who can let us down. Trust is a vital part of life without tech too, but tech seems to inspire and demand trust from us pretty quickly in ways we might not have fully thought through.

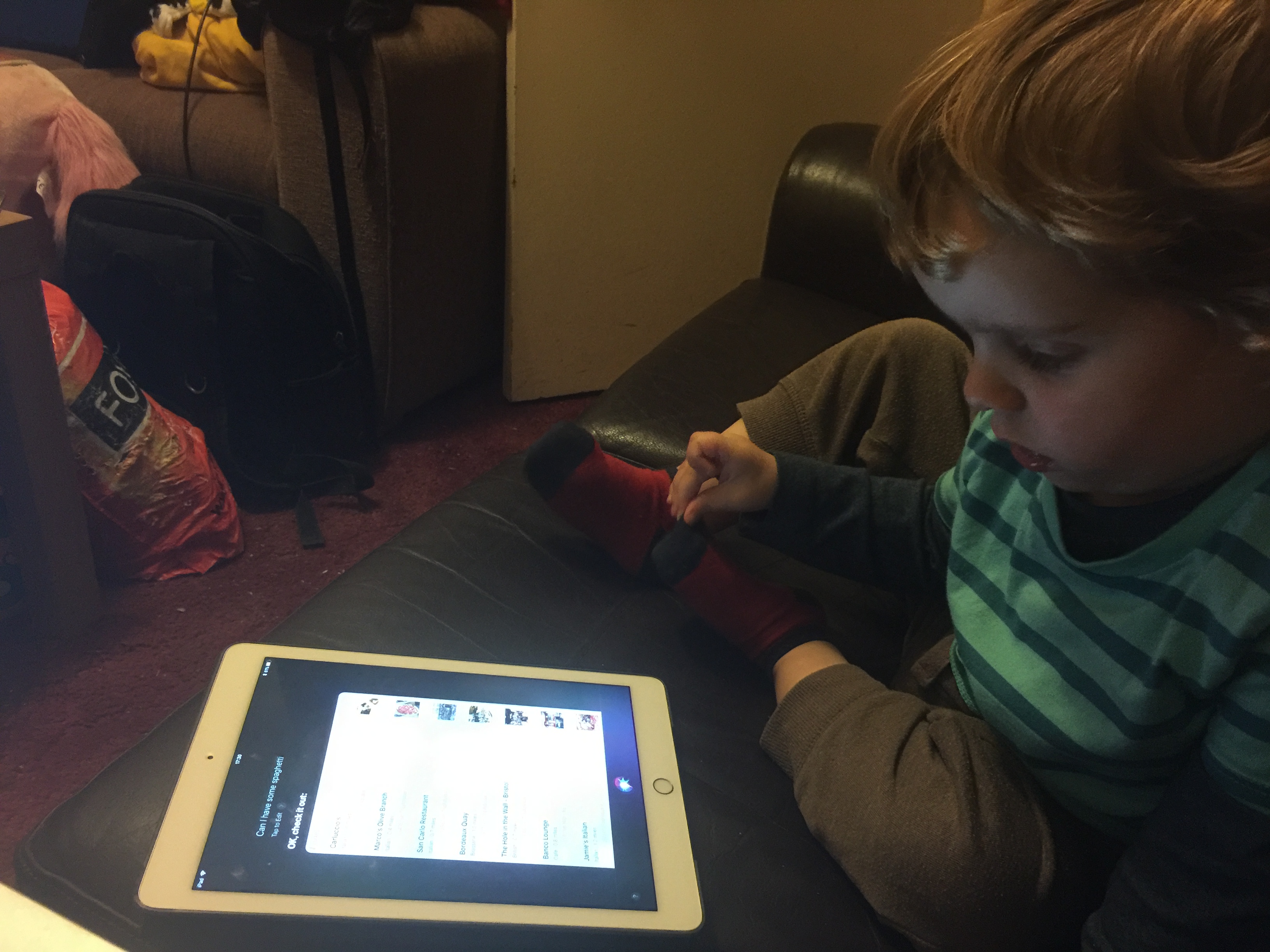

I’ve loved watching our three year old son start to get to grips with smart, connected voice recognition technology. It’s a way for him to explore the world and do things I couldn’t do before I was better at reading and writing. We do this together – we’re both learning how to use the tech well in a safe, satisfying way – but I’m struck by how quickly he trusts and confides in it, sharing what’s on his mind and in his heart. I’m also aware of how much we don’t really know about how all our data, voices, search results, likes, needs and wants are being used.

This is an area of sensitivity which is only going to grow as we enjoy and demand more from connected services. Sophisticated voice recognition alone needs massive amounts of data to be trained to work well. So does the processing of meaning in questions. Our brains interpret people’s meaning brilliantly. Machines are taking a while to catch up. If we want them to be useful, we have to trust them a lot. Siri in particular has a lot of catching up to do to be as smart, reliable and useful as its competitors, let alone reach the ideals of its designers.

So Apple needs our trust in massive, industrial quantities. We know it. We’ve already invested our trust through our iPhones, what we’ve used them for, and the amount of ourselves we keep pouring into them. Any story which suggests Apple might not be totally trustworthy is huge news, not just for them but – much more – for us.

2. The line between “us” and “them” is becoming scarily blurry

Are we cyborgs already? If iPhones were embedded in our heads to help us see, remember and process life experiences, the answer would be a definite yes. Does the fact that they are more portable and shareable than that make them less or more powerful as cyber parts of ourselves?

I would argue that when we trust smart phones as much as we do, it’s as if they are part of us. But while this is an illusion we can dispel fairly easily when we sell an old phone, when we buy a new one, we also buy another illusion – that we own this new piece of tech. Every so often, we get reminded that we don’t.

This is a huge issue connecting with the iPhone power management story. We think we’ve bought an iPhone, but we never really have the control over it that we think ownership should bring.

It’s the same with lots of technology that runs on code. We buy the box, but the code is always proprietary, owned by someone else, protected by law from our close inspection and tampering even if we have the skills to do so.

This feels very problematic, and brings up many questions concerning rights and responsibilities. Do we have the right to play with the things we’ve bought? What happens if these things cause us damage, or hurt other people? Where are the boundaries between my responsibilities and those of a tech company that asserts ongoing ownership of code that makes its devices work?

There are huge questions to be resolved here, possibly when tragedies occur as a result of ambiguities or misunderstandings. What will happen when someone gets killed by a collision with a car that had a driver, but was operating in “driverless” mode?

That will be huge news. Meanwhile, iPhone battery management seems pretty trivial in comparison. Yet it is news because it reminds us that these things we trust, this tech we carry, isn’t just gadgetry. It has become part of us.

1. Tech is more than our stuff, it’s part of our souls.

Someone tampering with code without our knowledge is not just risking our trust, but challenging our sense of selves, what we own, what we control, who we are and what we can do.

Maybe this sounds like unhealthy hyperbole. Perhaps I’m obsessed with tech more than I should be.

Maybe. But I think it’s no more than any other kind of treasured possession, and thousands of years ago Jesus reflected that “where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.”

Wasn’t he right? I don’t think he was just talking about money, but any stuff we value, and modern tech is designed to make us value it, for the good it can do for us and the amount of ourselves it can hold. iPhones are particularly good examples of tech we value for hugely important reasons.

There’s a lot more written about what tech does than what it means. It’s easier to benchmark performance than significance.

But stories like “Apple did something to your phone” resonate because of the meaning the tech has in our lives. Maybe that isn’t totally healthy. Or perhaps it’s a good sign that we are alive, sensitive to important things like who we are, and what we can do, in a connected world.

Maybe the best part of the story is simply that Apple apologised. They hardly ever do. They take pride in secrecy, and seem to believe this helps them make the stuff we want, but if what we really want is more than functional tech but the connection and the best of ourselves that we believe tech can bring, then tech companies need to get better at being the people we want to relate to. Putting problems right, building better relationships on the way, is a great way to start. If we ever believe their profits are more important than that, Apple – as big as they are – will be sunk.

It’s stories like this that remind me of ways we are unexpectedly connected, with our tech and each other. It turns out that trust is more valuable than money, good relationships are more important than good batteries, and we are all more valuable than our stuff.

Submit a CommentPlease be polite. We appreciate that.